An article by Liam Stokes, CEO of the British Game Assurance for www.unherd.com

You can read the original article here

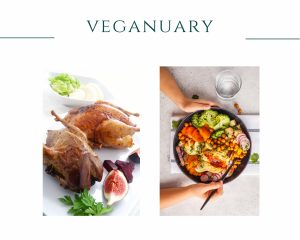

Diet is one of the stranger tribal signifiers in online culture, and each January the tribes go to war. Just as every Six Nations sees Twitter explode with dragons, roses, shamrocks and thistles, in Veganuary social media turns to steak emojis and little ‘v’s in circles to denote sides.

Country folk tend to be steak eaters and see in Veganuary a desire to alienate oneself from food, to pretend there can be life without death and food without bloodshed. Those of a conservative disposition tend to be for home and place and horny-handed sons of toil, and so don’t have much time for lab-grown burgers and insect bread.

But does the dichotomy need to be quite that stark? I have spent my working life in the game and wildlife sector; I have long argued that those of us who shoot and fish have more in common with vegans than we do with those frequenting the local drive-thru.

Earlier this month, Red Tractor research found the majority of shoppers don’t want to know where their meat comes from. That is not a tenable position for me. Throughout my career I have seen animals killed on farms, in the wild and in abattoirs, and pretending it doesn’t happen or hoping the animals didn’t suffer for the food I eat just doesn’t work for me.

So I have a lot of time for people who have thought about this, and decided to opt out of animal death altogether. Of course, such a thing is not really possible; copious birds and beasts die in the protection and production of vegetables and crops, but I don’t think this is quite the ‘gotcha’ it seems.

Livestock production sits on a different ethical plane to ‘pest control’. It involves a different degree of mechanisation and processing of sentient beings, with the abattoir as its starkest manifestation. Nearly all the meat I eat is wild shot game or wild caught fish, because I too prefer my food to have skipped the trip to the slaughterhouse.

However, I also believe livestock are essential in the British countryside. Regenerative agriculture, of the type championed by those who replace Veganuary with the somewhat hard to pronounce “Regenuary”, can only function with well-managed herds of livestock. Britain’s favourite rewilding project, Knepp Estate, produces 36 tonnes of meat a year from cows, pigs and deer as a direct result of its habitat restoration efforts. So consigning animal agriculture to history isn’t the answer either.

In the same way that it is possible to be a thoughtless meat-eater by ignoring the environmental and welfare implications of the animals we eat, it is also possible to be a thoughtless vegan by consuming nothing but processed products containing unrecognisable chemical ingredients and plant matter flown in from around the world. But there is also a way to follow either path in a sustainable and ethical fashion; I eat wild game and fish, and I would eat regeneratively-farmed meat, yet if neither are on the menu then I’ll be eating something that looks very much like it just might be vegan. In my experience if you try to do that then both paths end up looking rather similar.